Work to build a landmark new cancer centre in the heart of London reached a major milestone with a topping-out ceremony at Guy's Hospital.

The 14-storey, triangular-shaped building is set to revolutionise the way oncology services are delivered, having been designed with complete focus on the patient and staff experience.

Eighteen months into the build, and due to open late next year, the centre introduces a new 'village' concept to healthcare design.

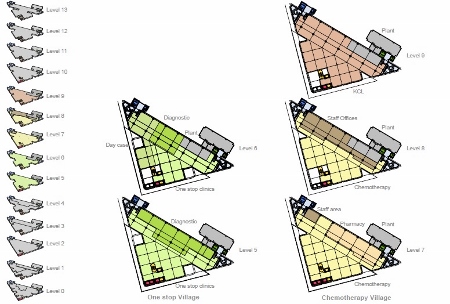

Instead of a tall tower block with lifts dropping patients off on each floor, the building is divided into four distinct villages, each spread between two and four floors and with its own colour and identity. Three lifts will take patients and staff from the welcome centre on the ground floor to the entrance of each village - a choice of just four destinations. Once within these villages, separate lifts and staircases will take them to the relevant treatment area.

Guto Jones, project leader at Laing O'Rourke, told BBH: "At the moment the existing Tower Wing lifts at Guy's can be problematic. People can be in the lifts for quite a while as they drop off and pick up people on lots of different floors.

"Part of the concept for the new cancer centre at Guy’s was to provide just four options, then once people are within the relevant village they can move around using internal lifts or the stairs. It makes wayfinding much easier and improves the patient experience."

A village feel

The four villages are the welcome village, which is split over two storeys (red); radiotherapy, which covers three floors (orange); a two-storey outpatient village (yellow); a three-floor chemotherapy centre and King's College London research unit (green); and a four-storey private patient facility (blue).

Each of the villages has been designed to be flexible and to adapt if cancer treatment methods change in the future.

Jones said: "Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust wanted flexibility within the design. We all know that cancer treatment is advancing and there is the possibility that, in 10 years’ time, some treatments currently in use won't be needed. The design provides flexibility so the spaces can be adapted and used for something else.”

The aim all along was to create a building that had an uplifting spirit, good access to daylight, and the ability to get fresh air, however high up the tower you go

The village set-up is one of a number of innovative design elements within the new building. Alastair Gourlay, cancer centre project director at Guy's and St Thomas' NHS Foundation Trust, explains: "Guy's and St Thomas' is a major provider of radiotherapy treatment in south east London and the South East of England.

"At the moment, treatment is delivered in 13 locations, across eight buildings and two hospital sites. This development is about having everything in one place and improving the pathway. Cancer treatment is not pleasant, but there is no reason why we can't make it easier."

At the beginning of the process, clinicians had raised the possibility of siting NHS inpatient and surgical services within the new building, but it was later decided the cancer centre would be for treatments such as radiotherapy and chemotherapy, and for outpatients appointments, not for operating theatres, which remain in the main Guy’s Hospital building.

From analysing the patient journey, the team quickly realised there were only a handful of reasons for cancer patients to visit hospital on any one visit.

The Science of Treatment

Gourlay said: "The idea was really clever. I think of the tower as a series of small buildings that just happen to be placed one of top of the other."

The entrance leads to a two-storey atrium, which will house a cafe, waiting area, reception, rehabilitation gym and staff facilities, and a service run by Dimbleby Cancer Care, which will offer advice, support and complementary therapies.

As within each village entrance, the main welcome area will not have a traditional reception, instead following the Maggie's Centre philosophy of a kitchen table-type reception where patients can sit alongside staff to discuss and plan their visit. Electronic sign-in technology will also be used.

Cancer treatment is a difficult journey, so bringing staff and patients together in a multi-disciplinary environment like this will revolutionise services

Within each village, the floorplan is split into two following the principles of the ‘Science of Treatment’ and ‘Art of Care’. The Art of Care areas are designed to be more social and interactive, with calming and hotel-style furniture and decor. The Science of Treatment zones house the more-clinical and technological facilities and, in line with patient requests, are more sparsely and cleanly designed. Ivan Harbour, partner at Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners, which designed the centre in conjunction with Stantec, said: "The aim all along was to create a building that had an uplifting spirit, good access to daylight, and the ability to get fresh air, however high up the tower you go.

"It's a very unique building and will set a precedent for the development of the rest of the Guy's Hospital site."

Access to outdoor space is provided through external balconies within each village. A significant arts programme has also been commissioned, overseen by arts consultants, Futurecity, and funded by the Guy’s and St Thomas’ Charity.

Creating a balance

Catherine Zeliotis, healthcare leader at Stantec, said: "This building was technically challenging, but it's about balancing the clinical needs with the human element.

"Cancer treatment is a difficult journey, so bringing staff and patients together in a multi-disciplinary environment like this will revolutionise services."

Also key to the success of the project has been Laing O'Rourke's use of modular and off-site construction methods.

Using Design for Manufacture and Assembly (DfMA) methods, many elements of the building and its structure were created in the factory, then brought to the site. This included the plant tower, which was craned into place in five sections.

Not only does this approach reduce the need for onsite storage, it also reduces congestion and disruption to services, and overall time on site.

Jones said: "This controlled modular approach is already being applied to other healthcare schemes and we will continue to develop its potential in the future."

Taking treatment out of the ‘dungeon’

The cancer centre is setting a precedent, becoming the first such development in the UK, and one of the first in Europe, to site radiotherapy treatment facilities above ground level.

A decision was made early in the design process to buck the normal trend of locating linear accelerators (LINACs) in the basement of the building. This was in direct response to early patient and staff feedback where a key concern was not wanting feel like they were being 'sent to the dungeon' for treatment.

The state-of-the-art equipment is traditionally placed underneath buildings so the ground can be utilised as part of the vital radiation shielding.

The architects, Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners, and Stantec, with main contractor, Laing O’Rourke, and structural building surveyors, Arup, were keen to set a new benchmark. As a direct result of the feedback, they devised an innovative solution enabling patients coming to the centre for radiotherapy to sit in a waiting area filled with natural light and views over London prior to, and immediately after, treatment.

Guto Jones, project leader at Laing O'Rourke, explains: "The centre will have six LINAC machines which had to be located on a single floor to improve the patient pathway. In most projects these would automatically have been placed in the basement, but the team wanted to respond to patient feedback, so we came up with a novel new solution."

The Guy's team was also heavily restricted in terms of space within the basement due to the need to protect and preserve a Roman boat buried beneath the site.

This was a ground-breaking design which took a lot of integrated engineering work and which is an exciting development for the future delivery of cancer treatment

Jones said: "All these factors meant we needed to look at locating the LINACs in the smallest-possible footprint, using innovative solutions like dense shielding for the walls and a direct entry into the bunkers.”

The walls were reduced in thickness from the traditional up-to-3mthick concrete structures, which would have compromised the available space considerably, to half the thickness by using high-density concrete modular blocks by US firm, Veritas. In addition, the patient will enter the bunkers directly, rather than using a long concrete maze, via a heavily-lead-shielded 10-tonne door made by the same firm.”

As the facility is based on the second floor, the substantial weight presented a huge challenge, with large 1sq m concrete columns added to carry the weight of the shielding and to make the building structurally sound.

Project director, Malcolm Turpin, of Arup said: “The extraordinary weight of the shielding means that, despite being only around a quarter of the height of London's iconic Shard building, the new cancer centre weighs almost the same.”

Another major challenge was ensuring enough headroom within the LINAC unit without unduly affecting the building. Usually standard floor-to-floor heights in healthcare facilities are around 4.2m. To accommodate all the equipment and associated shielding, the radiotherapy floors needed to be at least 6m in height. For the team this meant placing plant zones, rather than patient spaces, both below the linac zone and above it, so the height of the slab could be lowered or raised as needed.

Turpin said: "This was a ground-breaking design which took a lot of integrated engineering work and which is an exciting development for the future delivery of cancer treatment.”

Catherine Zeliotis, healthcare leader at Stantec, added: "Patients didn't want to feel like they were being sent down to the dungeon, so now as they wait for treatment, they get good views and, most importantly, can see daylight."

And Alastair Gourlay, cancer centre project director at Guy's and St Thomas' NHS Foundation Trust, told BBH : "This is the first time this has been achieved in the UK and, to my knowledge, one of the first times in Europe. We have already had other trusts from here and overseas visit the site to see what we have done and I expect this approach to be copied in the future."

Designed around the ‘Science of Treatment’ concept, clinical rooms are light and airy, but are more sparsely and cleanly designed

Iconic design and build approach

Like most of the country's iconic cathedrals, the new cancer centre was procured as part of a 'design and build' approach.

Traditionally, an architect will be appointed to create the design and a tender will then be put out to find a construction company that will deliver that vision.

Instead, Guys and St Thomas’ cancer centre project director, Alastair Gourlay, wanted to appoint a multi-disciplinary team that would be together from the very start of the project.

This led to the launch, in 2010, of an international Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) competition.

Gourlay told BBH: "I had undertaken a RIBA competition when working on the trust’s development of the Evelina London’s Children’s Hospital, which opened on the St Thomas’ Hospital site 10 years ago. That was the first such architectural competition led by the NHS.

We wanted a world-class cancer centre and you can't have that without world-class design

"When we decided we were going to procure a new cancer centre, rather than use a more-traditional design and tendering process, I thought it would be a good idea to use an RIBA competition again.

"We wanted a world-class cancer centre and you can't have that without world-class design." Following discussions with RIBA, Gourlay decided he wanted the contractor involved from the start.

"There are lots of things I don't like about PFI, but it has helped the industry to mature and I felt there would be value in bringing the contractor into the team from the very beginning," he said.

"It can only be a positive move to have everyone round the table at the start: to have the architect say they want to build this and the contractor’s reassurance of its buildability and affordability at the outset.

"In normal tender situations, you are focusing on which bid is cheapest, but this way the focus is on the quality of design."

In normal tender situations, you are focusing on which bid is cheapest, but this way the focus is on the quality of design

The competition led to the appointment, in 2011, of a team made up of construction and engineering firm, Laing O'Rourke; award-winning architectural fim, Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners; specialist healthcare architect, Stantec; and structural and building services design engineers, Arup. The £160m project is being largely funded by Guy's and St Thomas' NHS Foundation Trust, with significant grants from Guy's and St Thomas' Charity, the UK Research Partnership Investment Fund, Dimbleby Cancer Care, and additional cash from a public fundraising appeal.